In case you missed it, the rail map I made recently became somewhat famous. I’m calling that map draft #1 for now – there is more to come. Thanks again to everyone who shared feedback and support. For now I’m taking a break from transit to dig into another interest of mine: political maps. Who doesn’t love precinct-level data?

Gerrymandering is an incredible tool. It allows shrewd partisans to ensure that they don’t have to expend any effort convincing people that they should vote for them. It allows them to weaponize party loyalists to eliminate any influence of swing-voters (also known as people who can be swayed by good ideas and are trying to vote for the politician or policy idea that they think is best). Republicans have used gerrymandering across the country to ensure stable majorities in state legislatures and in the US House of Representatives.

2010 was a wave election year. Backlash against Barrack Obama and against the financial crisis led to historic gains for republicans everywhere. It was also a census year, which meant that political maps were being redrawn. Ohio swung from blue to red, giving republicans a once-in-a-decade opportunity to tilt the field in their favor until the next census. But what if it hadn’t happened that way? What if, instead, the democrats had the wave in 2010? What could Ohio look like?

Real quick: A primer on gerrymandering

Gerrymandering is the process of setting a political map for your party’s political gain. Historically, it was used to isolate and take power away from black voters. More recently, it’s being used to keep one political party in power. Generally in the 2010, republicans have been guilty of gerrymandering, but the democrats have been guilty of it too. Either way, it’s disgusting and should be illegal (more on that later).

Gerrymandering involves two basic strategies, known as packing and cracking. Both are focused on weakening your political opponents. When would-be gerrymanderers ‘pack’ votes, it means that they are trying to contain as many of their opponents’ voters into one district as possible. If you see a politician win with 70% or more of the vote, they’re probably in a “packed” district. The party that’s gerrymandering are ceding that district to the other side so that those voters won’t have much influence in other districts. The idea is that all of those votes are spent on one candidate, rather than on several.

In Ohio, you see packed districts in Columbus and Cleveland – these are areas that the GOP (when they drew the maps) packed with Democrats. They essentially said, “F*ck it. We’ll never win here, so let’s push as many dems into these districts as possible.” That’s why Erica Crawley and Kristin Boggs are able to win their House districts with about 80% support. Democrats have district 18 and 25 on lock because republicans have given up on winning there and they’ve stuffed as many democrats as possible in the districts.

Cracking voters means breaking up your opponents’ supporters so that they are dispersed among several districts. It dilludes your the other party’s votes to the point that they have little impact. In some ways cracking votes is more insidious than packing them, because it can totally erase the other party. It is a little more risky though and can sometimes lead to surprise outcomes, like when Tina Maharath won Senate District 3 by a narrow margin. The Republicans have tried to crack the Democrats in the Columbus suburbs by designing Senate districts 3, 16, and 19 so that the democrats are as diluted as possible.

Okay…Back to hypothetical rigging

The Ohio GOP have gerrymandered the US House of Representatives Ohio delegation to be 12 Republicans and 4 Democrats. They took a slight majority in 2010, and turned it into a 3:1 advantage. Crazy, right?

So, what if we lived in an alternate reality where the Democrats had power in 2010 and were able to gerrymander Ohio? What would it look like, and how far could the Dems take their 51% (in 2008) support among Ohioans? Could they take it as far as getting a majority in US House? Yes. And then some:

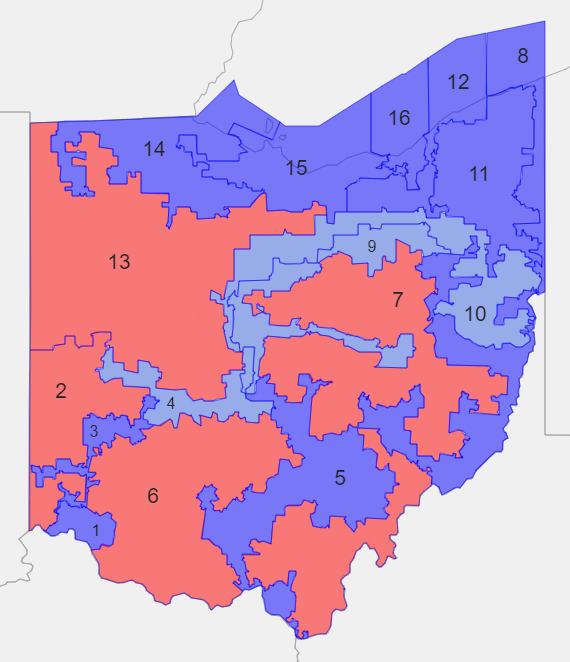

The maps above are one way the democrats could have redrawn of the US House of Respresentatives districts. The democrats would do everything they could to leverage strongly democratic districts. (One thing to note, the tool I used only has access to 2008 presidential election data, so technically, this map represents what the map could look like if the Democrats had a 51.5% majority in the state. It assumes that Ohio would have stayed kind of blue). The light blue district are swing districts that lean democratic, and the dark blue and dark red are strong democratic and republican districts respectively. Here’s the partisan breakdown for each of these hypothetical districts:

| District | Partisanship | Democrat | Republican |

| 1 | Good Democrat | 55% | 43% |

| 2 | Great Republican | 33% | 65% |

| 3 | Good Democrat | 55% | 43% |

| 4 | Fair Democrat | 54% | 45% |

| 5 | Good Democrat | 55% | 43% |

| 6 | Great Republican | 35% | 64% |

| 7 | Great Republican | 38% | 60% |

| 8 | Good Democrat | 54% | 43% |

| 9 | Fair Democrat | 52% | 46% |

| 10 | Fair Democrat | 53% | 45% |

| 11 | Good Democrat | 54% | 44% |

| 12 | Fair Democrat | 54% | 44% |

| 13 | Great Republican | 35% | 63% |

| 14 | Good Democrat | 59% | 39% |

| 15 | Good Democrat | 56% | 43% |

| 16 | Great Democrat | 80% | 19% |

Here’s the steps I imagined democrats taking:

- Split up democratic votes in cities and spread those districts outward as far into “republican” territory as possible, clipping off moderate and democratic enclaves along the way to make the district stronger while covering as much area as possible.

- Add strong republican precincts to the stretched out democratic districts until the democrats only have a 55% (or so) majority – still enough to be considered strongly democratic districts.

- For the remaining precincts, pack in as many possible conservative voters that you can into one district.

Notice that all of the “Great Republican” districts have the GOP getting >60% of the vote. In democratic districts, the margins of victory are smaller but still comfortable. In this alternate reality, republican precincts are either packed together or linked to strong democrats precincts in cities (packed or cracked). Cleveland was the only exception, where there were enough democratic precincts left over to make the district a veritable blue wall.

So, to summarize, if the democrats were able to gerrymander in Ohio, they could change the Ohio House delegation from a solid republican majority to to 4 Republican Districts, 8 Democratic Districts, and 4 swing districts that lean democratic, a solid democratic majority with the same voters. Moreover, it’s entirely possible they could give themselves an even greater advantage – I am just an amateur mapmaker, after all.

The key point is: This is the power of gerrymandering. You can take a slight majority or even a close minority and turn it into a supermajority.

It’s kind of wild that I’m able to take the current outcomes and totally flip it, giving democrats a 2:1 advantage over republicans.

In reality, the sort of gerrymandering exercise I did is what the republicans actually did in 2010, only with paid consultants and way more time/energy/money involved. This is why the Ohio Republicans seem invincible right now and are able to pass ridiculous abortion laws despite a lack of public support, bans on health education (we’re the only state that does so), and block cities from exercising local control. They have enough of a majority to win statewide elections and they’ve tilted the playing field in the legislature. They don’t have to worry about the votes because they rigged the General Assembly and US House elections. All they need to do is keep the lobbyist money coming, throw some red meat to supporters occasionally, and bash democrats when it’s election time (which has a knock-on effect of suppressing the democratic vote more).

But the law changed in Ohio, right?

Yes. It has. The Ohio GOP went so far in 2010 and voter outcry forced some changes for the 2020 redistricting cycle. Here’s how the law works:

- The legislature votes on a new plan. It’s adopted if 60% of members and at least 50% of each party support the plan

- If number one fails, a 7-person bipartisan group will try to put together a map. The map requires that 2 minority party members agree to the map

- If that fails, the legislature tries again, this time with requiring only one-third minority agreement

- Finally, when everything else has broken down, a majority of the legislature can pass a map (hint: the majority will be republican because the districts will still be based on the old map)

Here’s what I predict will happen: The Ohio GOP will submit a map that’s just as gerrymandered as the current map. They’ll claim that it would likely have the same electoral outcomes as the status quo, which many people will interpret as meaning that the republicans aren’t trying to change much. When democrats don’t sign on, the GOP will blame them for being implacable. “Democrats are trying to steal the vote!” They will know that democrats won’t accept a totally gerrymandered map, but they’ll get to cry foul and blame democrats for trying to obstruct the process.

It will be a long and drawn out process, but eventually we’ll get to step 3, the republicans will submit a map that is somewhat less gerrymandered but still totally unfair. They’ll claim that they were willing to compromise, but that democrats just aren’t willing to accept that they lost the election. Democrats will have to choose between accepting a not-quite-as-terrible map for 10 years or voting the map down and letting republicans draw whatever map they want for four years and then trying the process again then.

I think democrats will veto the map, and the Ohio GOP will short circuit the process and just pick whatever map they want for 4 years. We’ll go through the same process in 2024 and 2028. For those of us who will be watching closely, it will be clear that the GOP did not present a good faith map, but most voters may not be able to follow all of the threads. These maps are quite complicated after all, and the procedures of the General Assembly aren’t exactly gripping.

In short, the new law has not solved gerrymandering in Ohio. That’s why the most important race of 2020 is the Ohio Supreme Court. We need watchdogs on the court who will be able to challenge the maps once they are created, and ultimately, we’re going to need the court to declare that Ohio’s mapping process is unconstitutional (more on that in a later post).

What are Ohio’s alternative options?

In my mind, there is one decent system and one good system to end gerrymandering: The shortest-straight line algorithm and an independent commission.

A Decent System: Just let a computer do it

The shortest straight line algorithm is a process for building new political districts by having a computer draw the lines on the map. The programmer requires that all of the lines divide the population in half using the shortest-straight line. The idea is that you create the most compact and evenly populated districts as possible. Check out this video for a really great brief explanation. The final result looks like a shattered state map. Here’s what it could look like in Ohio (credit to Warren D. Smith and Jan Kok at rangevoting.org for building these maps):

Shortest straight line is good because it’s a simple algorithm that removes humans from the process. The results are simple, easily explained, and verifiable, but it doesn’t quite solve the gerrymandering problem. It’s still possible that the electoral outcomes could be out of line with the actual voting across the state. So, you could end up with a map that’s gerrymandered by a computer rather than by humans. It’s probably better than what we currently have, but is it optimal? No.

I would posit that a shortest straight line should be the map of last resort if (and only if) the legislature couldn’t agree on another map. If we can’t draw a good map, let’s use the computer’s. There are other options though.

The Good System: Rig the election for competitiveness

Even better than the shortest straight line would be to have an independent commission select the map. The commission would be tasked with building districts that are maximally competitive or representative of the overall vote. This video explains how it would work (it’s also a good primer on gerrymandering generally). The commission could create a map that represents Ohio voters (eg: would only give republicans, who earned just over 50% of the statewide vote a small minority in the Assembly rather than a super-majority). The districts could be more competitive too by creating many more swing districts where ideas could get fleshed out and voters could choose between opposing directions that the state could go in. Here’s a potential fairer map that Rich Exner from cleveland.com put together:

The map above has 4 solid democratic districts, 5 solid republican districts, and 6 swing districts. The groupings also actually make sense – you don’t end up with Lima and Oberlin in the same district. The results would also generally represent the overall votes of Ohioans: a slight republican majority.

No system will be be perfect, but a map drawn by an independent commission (not by a party) with the express purpose of representing the statewide vote and being competitive would be a heck of a lot better than the current system.

Ohio’s future

Gerrymandering is not a complex process. It implements fairly simple tools to rig votes. It can take a state that looks like a swing state on paper and turn it into one of the most conservative states in the country. It can allow for a minority party to hijack the legislative process. It leads to the passage of laws that most in the electorate disagree with, and it prevents legislation that people want from ever being considered.

We have to work to stop gerrymandering in Ohio. In 2020, we will need to watch closely and respond quickly when the Ohio GOP tries to create divisive maps. More importantly for Ohio’s future, we need to end the cycle of gerrymandering maps by electing new leadership to the Ohio Supreme Court who will once and fore all declare the process illegal and require that Ohio move toward a non-partisan process. More on that later…